Northsealand.

The land juts into the German Ocean, a skull-shaped vanguard fighting a losing battle against the waves. Here, it's hard to determine where the land stops, the sea starts, and the sky begins, and

all conspire against unwitting travellers, landlubbers and sailors alike. Boats lie beached on sandbanks and mudflats, while family homes perched on cliff tops have been abandoned and allowed to

tumble into the sea.

Villages are lost, and harbours silted up; where there's now sea, there once was land, and where there's now land, there once was sea.

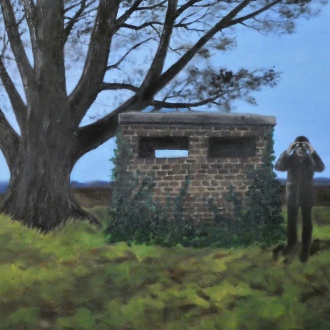

During an emergency Commons debate on March 18th 2003, Prime Minister Tony Blair spoke of an unpublished dossier he had access to which showed that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, and the means to inflict serious damage and loss of life to British citizens within forty-five minutes of the start of hostilities. If Iraq refused to comply with the United Nations proposals that it hand over these weapons, then Britain would have no alternative but to wage war on the Saddam regime.

We were spending a few days in Sussex at the time, and had driven up to Beachy Head. We parked up and had lunch in the car while we listened to the Commons debate on the radio. It was all very depressing. Robin Cook resigned, Claire Short didn't, and watching the TV footage later, it seemed to me that Blair had a mad glint in his eye, a deranged bellwether leading the flock towards the precipice.

As we walked along the cliff tops, the clouds rolled back, and the late afternoon light became dazzling - so dazzling, in fact, that we couldn't see the horizon - and everything seemed to be bathed in a vivid pink glow. I did several sketches and shot a roll of film with the intention of working the images up into a painting when I returned home. I didn't necessarily want to produce an anti-war painting, but wanted to get across the notion that against this quintessentially English backdrop, something disturbing was taking place. On the surface, it's a painting of a cute-looking sheep; but we, the onlookers, are the rest of the flock, and we have to decide whether to follow it for a few more yards over the edge, and into certain calamity.

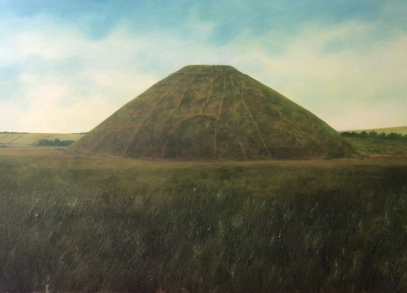

Perhaps the most important part of any journey is planning the route ahead, and arranging where to stay beforehand. On this occasion, we failed to adhere to this simple rule, and arrived at Avebury right in the middle of a crop-circle convention. Hippies from all over the country had gathered to beat bongos and hug standing stones, and there was no room in any of the hotels or guest houses for miles around, so we ended up spending the night in a farmhouse near Marlborough.

The next morning, we returned to Avebury, and stopped off at the West Kennet Long Barrow, an enormous tomb more than 300ft. long which had been in use for centuries and probably contained the bones of the ruling elite who ordered the building of Silbury Hill in the distance. This hill would have expanded millions of man-hours, and may well have taken nearly fifty years to build.

It certainly is a strange landscape, made even stranger by the fact that we know next to nothing about the culture which settled here and imposed their stamp on the environment.

And as we stood there awe-struck at these ancient feats of engineering, light aircraft were buzzing around in the deep blue sky, giving crop-circle conventioneers a bird's-eye view of patterns in the fields below.

Nobody knows exactly how old this figure is, or why he was originally cut into the chalk hillside. Records of him are sketchy before the eighteenth century, although it is feasible that he could date back to the dark ages and beyond. In many ways, it's rather like a centuries-old Angel of the North, acting as a sign of the beginning of the ancient path along the ridgeway of the South Downs.

I was surprised to discover that these days the outline of the Long Man is marked out with breeze-blocks, although it doesn't really detract from the overall sense of awe and anticipation you get when you first sight him.

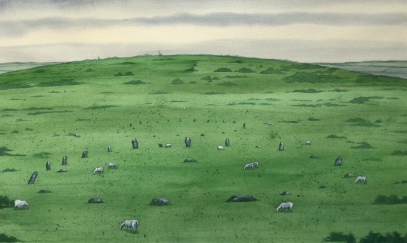

According to legend, these standing stones on Bodmin Moor are the remains of men turned to stone for playing hurling on a Sunday.

A grim, grey February day, and the burial mound of a local chieftain in the middle of a muddy field. I'm not sure if this tumulus dates from the Bronze Age, or whether it's Anglo-Saxon like the burial site a few miles away at Sutton Hoo.